Exploring Wildflowers Through Identiplant and Nature in Harmony

This year, I was fortunate to receive a BSBI training grant, which allowed me to take part in the Identiplant course. I am very grateful to the BSBI for the funding and the support provided throughout the course. I aimed to learn more about native species and improve my ability to identify plants in the field. At the same time, I began six months of surveying for the Nature in Harmony Project at Harmony Woods and the wider Diamond Woods. From April to September, I carried out 24 days of fieldwork, recording wildflowers as well as pollinators, butterflies, and birds. Identiplant offered a useful structure for learning about wildflowers, while the surveying project allowed me to apply what I was learning.

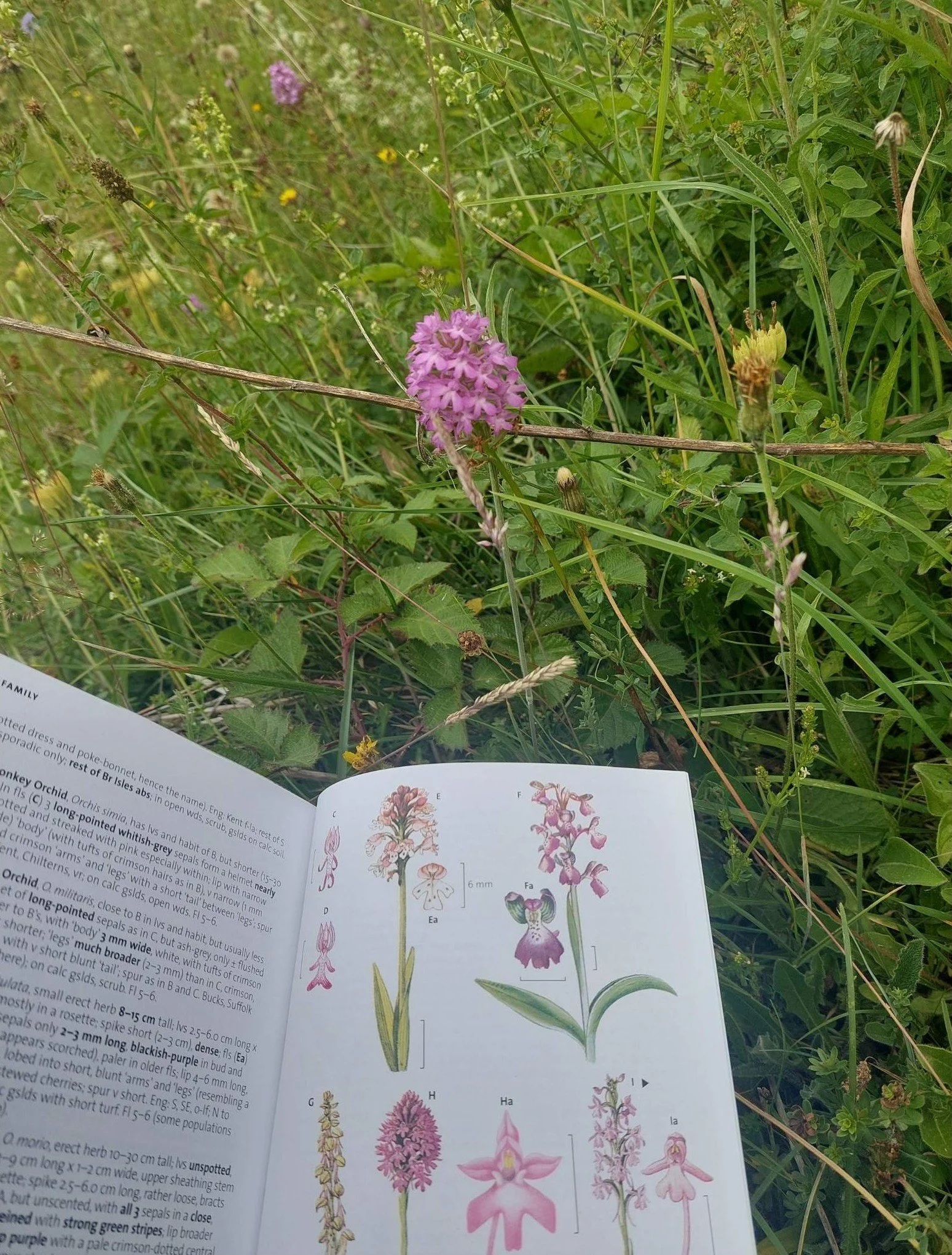

Wildflower Surveying at Harmony Woods, Andover on the 28th May 2025

The course itself is made up of 15 units and allows you to study different families in line with their flowering times. The first three focus on introducing botanical theory and terminology. The following 12 units each cover a specific plant family through information and question sheets. Each unit brought the challenge and excitement of finding different plants. I was also assigned an experienced local botanist as my tutor, who provided feedback and support throughout the course.

Most weeks, I’d read through the information sheet and then head out with a 10x hand lens, my camera, and a copy of Rose’s ‘The Wild Flower Key’. These wildflower hunts became an enjoyable way to discover different families and observe the changes throughout the seasons. It could be challenging and I often spent hours walking in search of plants. It was very satisfying to find a new species.

One of the first families I studied was the Brassicaceae (Cabbage) family in Unit 4. It wasn’t a family I had paid much attention to before and I quickly discovered just how similar some species within a family can first appear. I learnt to recognise the family by its flowers with four equal petals arranged in a cross, and four sepals among other features. Closer observation allowed me to identify species. For example, Arabidopsis thaliana (Thale cress) has long, very narrow, cylindrical fruits, details I may have overlooked before.

The flower and fruits of Arabidopsis thaliana (Thale Cress), a plant from the Brassicaceae

As I moved through the next few units, I learnt how to recognise differences between closely related species. In Unit 6, I studied the Liliaceae (Lily) family and learnt to tell apart two bluebell species. The Hyacinthoides non-scripta (native Bluebell) has nodding bell-shaped flowers with cream anthers. The flowers hang from one side of the raceme. In contrast, H. x massartiana (hybrid Bluebell) stands upright, with flowers arranged on both sides of the stem with blue/whitish anthers. Once I knew what to look for, differences between species became very clear.

The same applied when studying the Ranunculaceae (Buttercup) family in Unit 5. Closely related species such as Ranunculus bulbosus (Bulbous Buttercup), R. acris (Meadow Buttercup), and R. repens (Creeping Buttercup) look similar at first glance, but can be distinguished by features like whether the sepals are reflexed or spreading, the presence of runners, leaf shape, and differences in the flower stalk. Comparing these differences during field surveys was a really rewarding way to apply what I had learnt.

One of my favourite things about the course was how it encouraged me to pay closer attention to plants I may have once overlooked. For example, in Unit 12, I was introduced to Odontites vernus (Red bartsia), a hemi-parasitic plant from the Orobanchaceae (Broomrape) family. Initially, it seemed unassuming but when I looked more closely, I found a beautiful branching raceme of pink flowers.

Odontites vernus (Red bartsia)

As spring turned to summer, the calcareous grassland at Harmony Woods came into full bloom. I had never visited this habitat during the summer before and was amazed by the variety of plants and butterflies. This rare habitat, found only in north-west Europe, can support over 40 species per square metre and relies on ongoing management to prevent scrub encroachment.

The chalk mound at Harmony Woods. Seeded with wildflower seed in 2017.

It was here, in this rare habitat, that I studied the Fabaceae (Pea) family, in Unit 9 and became aware of its diversity. I learnt to recognise their distinctive flowers with their ‘standard, wings and keel’ petals. Lotus corniculatus (Bird’s-foot trefoil) was low growing with yellow flowers with orange streaks, while Onobrychis viciifolia (Sainfoin) bore pink flowers with red veins arranged on slender, upright spikes. Visting the same transects every month allowed me to see how Fabaceae species changed throughout the seasons and to identify differences in their seed pods.

In chalk grassland, I also studied species from the Rosaeceae (Rose) family in Unit 10 such as Agrimonia eupatoria (Common Agrimony) with its bright yellow flowers. I observed how this species has cone shaped fruits with hooked spines adapted for seed dispersal, giving me insight into the plant’s ecological adaptations. I also investigated the Lamiaceae (Deadnettle) family in Unit 11, where I studied their diagnostic features, including distinctive square stems and leaves in opposite pairs. I found Prunella vulgaris (Self-heal) with it’s beautiful blue-purple flowers in dense oblong clusters and Clinopodium vulgare (Wild basil) with its dense tiered pink flower whorls.

Later, in Unit 14, I explored the complex Asteraceae (Daisy) family, understanding how to compare features such as flower size, involucre shape, and growth form. Centaurea nigra (Common Knapweed), was buzzing with many insects. This was a reminder of how important these wildflowers are for pollinators.

Vanessa cardui (Painted Lady) butterfly feeding on a Centaurea nigra (common knapweed) flower on the chalk mound at Harmony Woods.

By spending time with these plants, I became familiar with their diagnostic features and developed a deeper appreciation for what makes chalk grassland such an exceptional habitat. Completing Identiplant alongside this surveying project has helped improve my confidence in recognising species in the field. Now that my survey season has ended, I look forward to contributing to the Nature in Harmony database and sharing the results of my survey season.